The Imagination of Survival: A Conversation with P.K. Dalangin

On abandonment, imaginary friends, and writing stories that remember for you.

There are writers who entertain. Then there are writers who unearth—the ones who reach into silence and offer it language, shape, and pulse.

P.K. Dalangin, or Paula, is one of the latter.

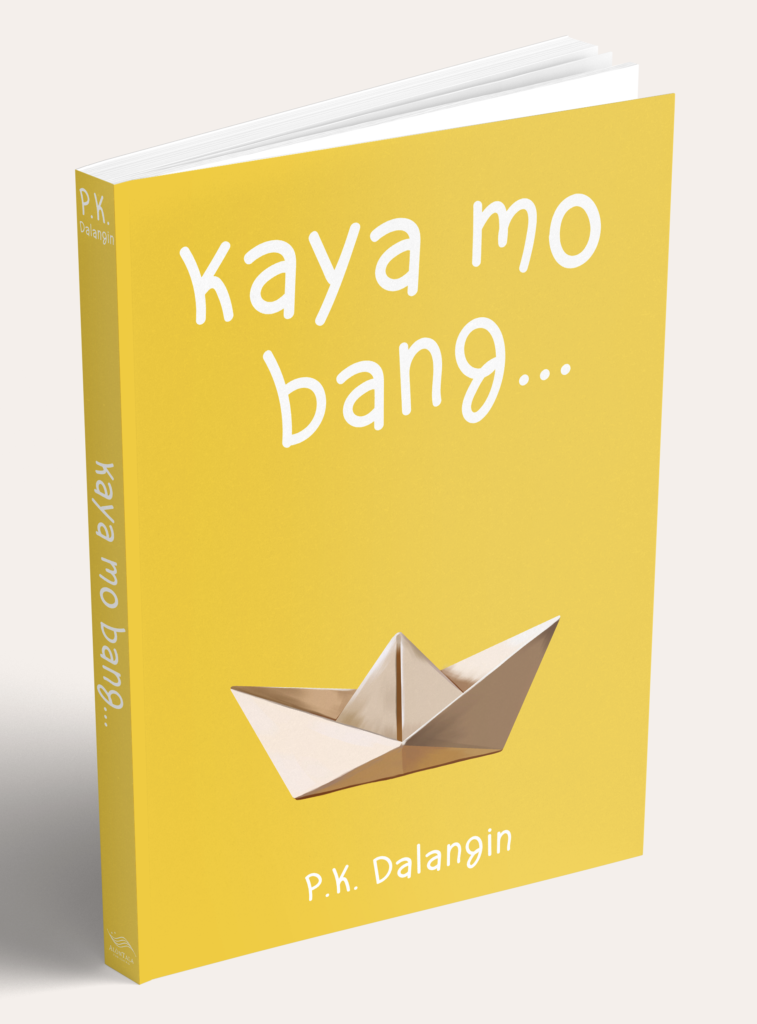

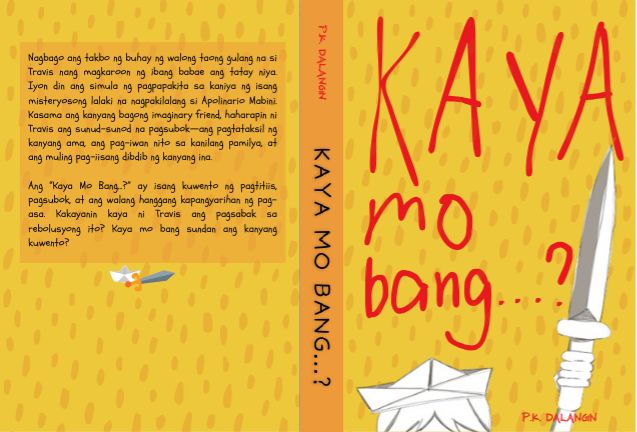

In her debut novella, Kaya Mo Bang…?, she tells the story of a boy named Travis and his invisible companion, Apolinario, as they navigate childhood heartbreak, broken family systems, and the kind of grief that hides inside mango trees and after-school silences.

But this isn’t just fiction. It’s a reckoning. A quiet revolution in Tagalog, dressed as a coming-of-age story.

In this interview, Paula opens up about what called this story out of her, the emotional weight of writing it, and the invisible truths many Filipino children carry but are never allowed to say. What follows is not just a behind-the-scenes look at the book—it’s a portrait of a young author daring to believe in her voice.

1. What called this story out of you? Was there a moment it demanded to be written?

Last year, I saw a June Writing Challenge from one of the publishing houses I follow on Facebook. That time, I really wanted to do something productive because it was my semester break. Then I thought, if I really want to be an author someday, ano pa ba hinihintay ko? To improve more of my skills sa writing classes na tine-take ko? Then it hit me: I have to start writing now for the future career I want.

I tried so hard to come up with a really unique storyline that I can sell—something that will make people read my book. I wanted it to be a sci-fi novella or a collection, pero hindi pa talaga ako gano’n ka-experienced sa pagsusulat sa genre na ’yon. Then one day, while commuting somewhere, the idea hit me: I should write something familiar to me—na kahit pa hindi ako experienced writer, I can finish it. And I wanted to write in Filipino kasi mas madaling maportray yung emotions ng Filipino characters if they’re speaking sa language natin.

At that time, I was also sad about my brother going away to work abroad, kaya all I could think of was missing him—because we’re really close. I didn’t want to be the main character of my story, kasi I’m better at observing and knowing people more than self-reflecting. Then I thought about his background as a person. Kapatid ko siya sa mama, so he had a very different childhood than me, and sa Pangasinan siya lumaki. Then the ideas just flowed naturally. He is a product of a broken family—which I never really talked about with him—and I think that concept alone is worthy enough that it demanded to be written.

2. “Kaya mo bang…?” is both a question and a dare. Why did you choose that as your title, and what are you still daring yourself to face?

Thinking about kids as characters in my story, I had to go down memory lane. Ano ba yung mga laro namin noon, and paano kami mag-usap-usap ng mga kalaro ko? Then I remembered—kids love challenging each other out of nowhere. “Kaya mo bang akyatin ‘yang puno?” “Weh, sige nga.” —conversations like that really capture those random moments of being bata (at least in my experience). It turned out to be a good choice, too, kasi tumugma siya sa challenge ng main character sa novella ko—how he faces something he’s unsure he’ll survive.

Personally, a thing I’m still daring myself to face is believing in my own work and being confident in what I do. I’m always doubting myself—tama ba yung mga ginagawa ko? Is it something to be proud of ba? Up until now, I don’t even have the courage to share with other people that I’m working on this novella to be published this year. I’m scared that if they read what I write, it means I can be subject to criticism. And while I know criticism is good for improvement… I’m not ready yet for the public view of me as a writer.

3. Was there a scene or chapter that almost didn’t make it in? One that felt too personal, or too raw?

Actually, I kept every scene and chapter that I wrote. I think each one serves a purpose in telling Travis’s character and story. Even though some parts are personal, I’m taking a leap of faith that people will pick up the story and somehow be inspired by it—especially if they’ve gone through the same background and challenges as Travis.

And I think my kuya would be really proud of what I wrote. He always is.

4. Writing about family betrayal, especially through a child’s eyes, is emotionally loaded. How did you protect your own heart in the process?

It was really loaded and emotional for me to write. I did cry while writing at some points—and that became my way of protecting my heart in the process. Writing is cathartic for me, and if it gets masyado nang heavy, I have to pour my emotions out. Just cry.

Write what you want to write—because that’s what fuels ideas: emotions.

5. What do you think readers will feel first—grief, nostalgia, or anger? And which of those did you wrestle with the most while writing?

I think they will first feel nostalgia—probably their childhood: yung simpler times na nakikipaglaro ka pa sa labas, no cellphones, habulan, babad sa araw. These experiences are universal. Siguro if they read my novella, it will bring them back and push them to reflect on their own childhood memories, and appreciate the little things that contributed sa growth nila ngayon.

The feeling of grief really hit me while writing—even if it wasn’t a first-hand experience. As I imagined Travis, a 10-year-old boy na dumaan sa ganitong situation, with no clear explanation kung bakit sila iniwan ng tatay niya… it was very difficult. I weep for those who had to go through that. I’m lucky enough to have a supportive father, and I just wish sana lahat ng bata may both parents like me. But we can’t change that.

What we can offer is support. And maybe that heartbreak as a child—being a product of separated parents—is what will make them stronger, and more ready to face challenges paglaki.

6. How do you know when a scene is emotionally true? What’s your internal compass?

Minsan, pag nagsusulat ako, I push myself not to take breaks kasi I know if I stop, I might leave what I’m writing and tamarin na. Pero whenever I write something emotionally true, I pause. I read it over and over again, and I just think, “It feels right.”

Or minsan, I’ll feel sad reading what I wrote. That’s how I know it evokes authentic emotion.

7. Let’s talk about the Imaginary Friend. What does he really symbolize?

Imaginary friends are kind of overused sa children’s stories—usually acting as emotional support, or guiding them to grow and stimulate their creativity. But I wanted something new.

I even considered creating a famous celebrity or cartoon character that could appear in my novella—but of course, we have to think about the connectedness of every aspect of the story. In the end, I landed on a historical figure.

I’ve always had a fascination with the character of Apolinario Mabini. He’s considered the “utak ng Katipunan”—a brilliant tactician in the revolution, a respected adviser, and honestly, I find his lines in historical films so poetic. As an imaginary friend, he’s able to guide Travis—advise him—without physically helping him. Just like in Philippine history, he becomes a symbol of inner strength and wisdom.

Kasi, we can also say that ang buhay ay isang rebolusyon, and hindi natin ‘to kaya nang mag-isa. That’s why we have friends. And family.

8. The story blends harsh domestic realism with a soft touch of the surreal. Was that balance intentional, or did it emerge naturally?

I was really aiming for the magic realism genre kasi it’s one of my favorites.

While writing the novella, hindi ko naman masyadong inisip yung pagka-balance ng realism at surreal. It just flowed naturally. Pero while I was planning the plot outline, I included some true events that are vital to the story. Then I added some surreal aspects na makakapag-elevate pa ng reality na nandiyan na.

In the end, I don’t know if I really answered the question, hahaha. I guess it’s a balance of intentional writing and natural storytelling.

9. You’re working in Tagalog, but the themes feel universal. Did you ever consider writing it in English? Why or why not?

When the idea about a broken family came to me, I just knew I needed to write it in Tagalog.

As I said earlier, I’m writing about something familiar—so the way to bring out that familiarity even more is through our own language. Considering na yung characters din are Filipino, and the setting, it would feel kind of awkward to evoke emotions in readers in English.

Kasi sa umpisa pa lang, Filipino ang mga magbabasa. And gusto kong maramdaman talaga nila yung story.

10. What part of yourself lives in Travis?

I guess I’m the kind of person na sinasarili yung problems ko. As long as I can still keep it in and not bother the people around me, I repress my emotions. I don’t like people worrying about me—and on the other hand, I worry about other people’s feelings too much.

Travis is a kid who has gone through a lot, and I think we can all find a piece of ourselves in his character. In some way, we’ve all been that child.

11. How has writing this story changed you—not just as an author, but as a person?

It changed me in a way that I’m slowly believing in my work. Slowly, I’m starting to see that kaya ko naman palang magsulat—and that I should be proud of my work, even if it’s not perfect. (Thanks, AlònTala, for putting trust in my piece.)

Also, writing this novella inspired me to write more about the things left unspoken in our society. Kids are being put through too much trauma. The unpacked family baggage. The issues we rarely talk about. I always thought I wouldn’t be that kind of writer—but there’s something deeply fulfilling when you write scenes that give a little bit of your voice to the characters. It’s… somehow magical.

12. What stories were missing when you were younger that you’re now trying to write?

When I was younger, I didn’t really read stories. I spent most of my time playing outside with other kids. Pero if I was a reader back then, I would’ve loved reading novellas written for young readers, pero mga istorya na minumulat na yung kaisipan natin sa mabibigat na issue.

I always tried not to cry as a kid, kasi ang turo ng mama at papa ko: ‘Wag iiyak, dapat matapang lagi. Kids only rely on what their parents say. Pero if I had books that told me, “It’s okay to feel these things. Cry. Talk it out with your support system,” I think I’d be way different from who I am today.

Maybe better. But to be honest, I won’t change anything. Because it made me who I am. And I’m fine with that.

13. Were there any moments you felt like giving up on this manuscript? What kept you going?

Most of the time, I felt like giving up… because I just wanted to enjoy doing nothing. (It was school break, after all.)

But I also wanted to do something I’d be proud of someday, and I knew I shouldn’t keep making excuses to delay it.

Isa pang naging motivation ko sa pagsusulat ay yung kuya ko talaga, na aalis na para magtrabaho abroad. I wanted to give him the manuscript as a gift before he left. Although in the end, hindi ako nagkaroon ng courage na ipabasa sa kaniya ’to, I know someday he’ll finally read it—and be proud of me.

Of course, same with my dad, who always supports whatever I do.

14. How did you navigate writing about trauma with care, not exploitation?

To be honest, it’s really difficult to write about trauma—especially when it’s not your personal experience. But I’ve always been an empath. When I put myself in someone else’s shoes, I at least get to feel a portion of what they feel.

I guess I handled it with care by chopping the huge subject into parts, and working on it at a slow pace. Binibigyan ko rin yung sarili ko ng time to reflect on certain events. I weigh whether I should include something or not. I change some things to make it more fictional, but still tell the truth in a way that’s not too raw.

Never kong naging purpose ang pag-eexploit ng story for fame or money. In the first place, what really started my literature journey is passion. I want to tell a story. I have a story to tell. And even if people won’t appreciate what I do, at least at some point in my life, I made something beautiful—immortalizing feelings, people I know, and events close to my heart through my writing.

15. There’s a kind of shared ache in this book—poverty, masculinity, silence. What aspects of Filipino family culture were you consciously interrogating?

Definitely silence. I grew up in a house where we didn’t talk about problems that much. When we were financially struggling, my dad didn’t want me to feel that he couldn’t support me or give me everything I wanted. On the other hand, my mom always shushed me when I cried. She’d get mad—even if the reason I was crying was valid.

Kaya na-train ako to hide my feelings. I grew up worrying about them patago. I still remember, hindi ko sinabi sa kanila noon na nabubully ako sa school. They only found out from my teacher.

Going back to Travis’s story, it’s really built on that concept of silence. It’s about my brother, being a product of separated parents. He never talked about it. My mom never told me the full story. Sometimes, details would just slip out in conversation, and I’d piece them together and make up the rest.

Although my brother grew up well in the care of my dad, I still wonder… did it hurt when he was a kid? What does he feel that he doesn’t tell me about his childhood?

In reality, that’s one of the negative aspects of Filipino family culture: we don’t talk about what bothers us. The things that make us mad or sad, we just keep them in. But at some point, all those feelings resurface in ways we can’t always control.

16. What’s something about growing up in the Philippines that people outside might not understand, but is essential to this story?

I think Filipino family dynamics are something outsiders might not understand. Sometimes, kids become vulnerable to trauma because of how they’re exposed to family issues.

Hindi naman ’to pinag-uusapan. Hindi ine-explain sa bata nang maayos if ever may problema ang parents, and hahayaan lang silang maapektuhan implicitly.

This is a very essential part of the story. It’s the root of Travis’s internal conflict. He had to face those challenges, unpack the trauma, slowly open up, and eventually—grow.

17. How do you hope this story contributes to contemporary Philippine literature?

That is some heavy-ass question T~T.

But I think, in a way, it can influence how we think about what we write. We should start including young characters in heavy issue narratives—because even if they’re young minds, they need to be ready.

And one of the most effective ways to help them? Through literature.

18. Who do you imagine reading this ten years from now? What do you want them to remember?

I actually imagined my readers to be around 11–14 years old. It’s that phase in life where they’re most vulnerable to influence.

I hope they can find comfort in Travis’s character—as well as in Apolinario—because together, they can teach young readers how to navigate heavy emotions.

19. If Travis could say something directly to a reader his age, what would it be?

I’m gonna attempt to write in Travis’ voice…

Hello! Ako nga pala si Travis.

Nakakilala pala ako ng bagong bespren pero ‘di siya nakikita ng iba. Apolinario pangalan niya. Pero kahit ‘di inviscible si Apolinario, malaki tulong no’n sa’kin.

Sabi niya, kailangan ko lang may kausapin ‘pag mahirap na huminga, ‘pag nakakaramdam ako ng lungkot. ‘Yung parang sumisikip ‘yung dibdib.

Sana ‘di niyo ‘yun nararanasan kasi ‘pag nangyayari ‘yon, ‘di ko na alam gagawin ko. Pero basta may mahahanap kayong kausap na mapagkakatiwalaan o kaya matalik na kaibigan, magiging okay din ang lahat.

‘Pag invisible sila at nakakabasa ng isip, mas okay ‘yun!

20. What’s next for you? What story is whispering to you now?

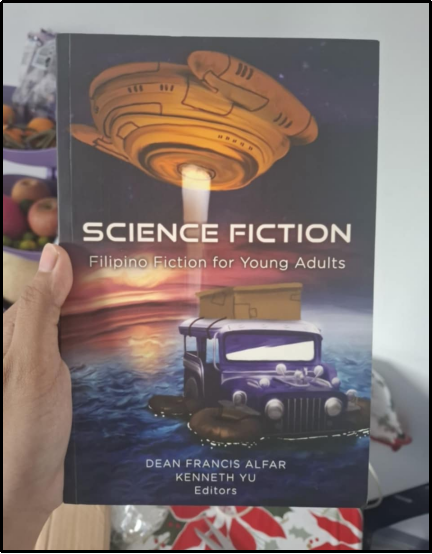

I’m still stuck on writing short stories every time I have a sudden creativity burst. Sa ngayon, I want to lean more into sci-fi kasi ‘yun yung undergraduate thesis ko, and I find it really interesting kung paano nagkakaiba ang sci-fi ng West at ng Pilipinas.

We always try hard to follow their tropes and trends, but we are from Asia, and we have a different culture. So I guess I’ll try to incorporate more Filipino culture and identity in sci-fi short stories.

Kasi… it’s fascinating to speculate about our future as Filipinos.

21. You’re currently studying Literature at CLSU. How has your experience there influenced the way you tell stories?

My professors always say, “The more you read, the more input.” The readings from my classes really influenced my writing style. I take aspects from different kinds of writers and stories.

But what changed me more is how I now appreciate Philippine Literature—and the need to tell significant Filipino experiences and struggles. Medyo Western-centered kasi yung taste ko before. I only consumed English novels, I’d buy from Booksale, and I wasn’t really exposed to Filipino writings.

In addition, I actually get more from the people I meet than from the classes I take. I get inspiration from my friends in college, and through simple observation, I build stories or characters from that.

Also, my professors—who believe in my talent—inspire and motivate me even more to really pursue a writing career. I love the people who surround me here at CLSU. I feel that I belong, and it makes me happy to be with people who make literature come alive.

22. Nueva Ecija often exists quietly in the background of national conversations. How does being a Novo Ecijano shape your perspective as a writer?

As a Novo Ecijano, we’re not exposed to the culture of Manila… with people who seem to exist in a completely different world. We’re surrounded not by city lights, but by rice fields and a rural lifestyle that gives a distinctly Filipino experience.

Kids stay under the scorching sun, maliligo sa patubigan ng bukid, takutan sa mapupunong lugar kapag gabi na. We’re raised differently.

Living in Nueva Ecija gave me a different perspective because of the place, the people, and how they live. And I want that to penetrate the city-saturated settings we often see in national literary conversations.

Also, I think being a Novo Ecijano shapes me as a writer because I still seem to stay in touch with the stories and struggles of those around me.

23. If you could give one message to the emerging creatives from our province—those quietly writing poems, painting canvases, building dreams—what would it be?

Take inspiration from what’s around you. Don’t try to catch up with the popular creatives or trends in writing. Instead, take inspiration in your surroundings.

Observe people. Find the story that could arise from those observations.

Living in a province gives you a unique perspective—something that can’t be replicated. If you think life in the province isn’t interesting enough to be the subject of your work, make it grand.

Don’t stray away from your roots. Because familiarity can spark something special.

EXTRAS

● A scent that reminds you of childhood?

Vicks VapoRub. My dad always has it. Pinapahid niya sa ulo niya, anytime of the day. Lalo na pag kararating niya ng bahay pagkatapos mamasada ng tricycle. That’s why I always keep it with me now. It’s soothing… and nostalgic.

● If pain had a flavor, what would it taste like?

Bitter.

Parang tutong sa kanin na nasunog—hehe—but you have to eat it anyway, because your mom won’t let you waste food, and it’s your fault the rice got burned in the first place.

● Song that would play during the book’s final scene?

Definitely “Wag Kang Matakot” by Eraserheads!

● One line from your book that still guts you when you read it back?

“Itong ilog ang buhay natin… sasabay tayo sa agos ng buhay, may mga pagdadaanan tayong mga problema at ito ’yong mga kalat sa ilog. Mga stick na puwedeng makatusok sa atin. Minsan, hindi gano’n kabilis ang agos ng tubig, pero patuloy tayong uusad.”

P.K. Dalangin writes with the rawness of someone who’s been told to be quiet all her life—and is finally answering back through story. Kaya Mo Bang…? is more than a book. It’s a whisper to the child in all of us. The one who didn’t understand why dad left, who was told not to cry, who made up invisible friends to feel seen.

To read her is to remember, to feel again, and to grow.

This is only her beginning—but already, she’s giving language to what so many never had the chance to say.

Her book releases this September. Until then, let her words keep you company.